As it currently stands, I am wearing fuzzy socks and warm pajamas, on the evening of the ninth biggest snowstorm in Philadelphia’s history. I’ve baked a quiche, pan-fried sweet potato pancakes, have gorged myself on coffee and Triscuts and goat cheese and beer, because there is no excuse quite as convenient as a blizzard to spend an entire day eating and drinking and cooking in your fleece-lined socks.

As it currently stands, there are twelve reported deaths in the United States as a result of this snowstorm. The usual suspects. A man had a heart attack while shoveling. The rest died in auto accidents. People of all ages. One child, a boy, four years old.

I am thinking about this because of this paragraph, written with humor and eloquence by David Dudley in yesterday’s New York Times.

There’s something cartoonish about the menace of a blizzard, in which nature’s wrath assumes a fluffy, roly-poly form and tries to kill you. It’s the meteorological equivalent of getting smothered in , or attacked by the . And yet, kill it does, via car accidents and heart attacks and other misadventures, usually involving people trying, unwisely, to do something.

I am thinking about this because I am lucky to be inside right now. I am not a doctor or a nurse, or anyone who keeps an emergency room or an intensive care unit safe during a time of crisis. I am not a person who plows roads, or drives large trucks containing massive quantities of rock salt. I am not a police officer, a firefighter, or an ambulance driver.

I’m also not a barista, a line cook, a chef, or a waitress. I’m not a bartender. I’m not a cashier at Wawa.

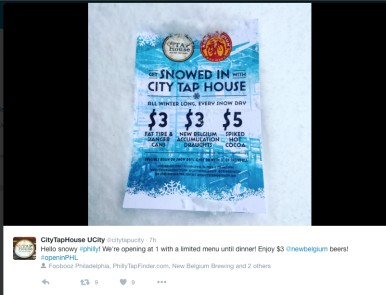

Those are, for the record, all of the people who made their way to work in a snowstorm because their places of business decided to stay #OpeninPHL.

I’m a writer and a blogger, and I am also a theatre artist.

And today, I’m glad that I didn’t have to go to work, something that was not afforded to many of my colleagues and fellow theatre artists. Today, I snuggled under the blankets and slept in, while my friends trudged through the snow to rehearse, or to perform for minuscule audiences. To sell concessions and tickets, to unlock the theatre doors, to control the lights and the sound.

And I know it can be fun, because I’ve been there before. I’ve done the trudge-through-the-snow, show-must-go-on, do-or-die-to-make-the-art thing, and it’s an adrenaline rush. It’s a team building exercise, and it’s an amazing feeling: to walk to work feeling like you are the last human alone in a quiet, wintery world, a world that looks so very different from the one you inhabited just a few hours before. I’ve even been in those audiences, those “come see the show for free if you can make it here” shows, when it feels like a performance that exists only for you — which of course, in a sense, it is.

I also work for a small theatre company, and I’ve served as a producer, a marketing director, and someone who sees the effects that a natural disaster can have on a bottom line. Who knows exactly how many rehearsal hours are allotted, and knows there are almost never enough. Knows how precious those tech-time hours are. Knows how financially disastrous a show cancellation can be.

We are taught that the show must go on. We listen to stories that are passed down, instilled in us as heroic myth, bragging rights in an unnamed competition: the show when the lead actress performed concussed; the time when the actress kept tap-dancing while bleeding; the time when the actor passed out after his curtain call because he had a hundred-and-three-degree fever. If you work in this business, you know these stories. Chances are, you have one yourself.

And it’s here that I remind you, my fellow theatre artists, that you are not doctors. You are not ambulance drivers or snowplow operators. You are musicians, artists, singers, and dancers. You are technicians and stage managers, designers and stagehands, janitors and salespeople, mothers, fathers, students and teachers. You create beauty and joy, you make people laugh and cry, you teach and instruct and you create delight and you share it with others, and you can’t do any of those things if you’ve gotten into a car crash on your way to the theatre.

I say this not to throw stones at those of you who went to work today. I am sure that for those of you who performed today, some of you feel exhilarated. You’re swept up in the rush of getting the job done, and that’s a great feeling, and I don’t mean to shame you away from that. I don’t want to take that feeling of pride and achievement from you.

But we’d be having a different conversation if one of us got hurt. It would be a different story if someone was injured on their way to work, one of the unlucky few that inevitably do make headlines in the aftermath of every major snowstorm. There’s a version of this scenario that doesn’t end with high-fives and everyone going out for snow beers, and it’s unlikely, but it’s possible, much more so than on any day of the year. The risk is greater during a snowstorm, and so we collectively need to decide whether or not that risk is worth it.

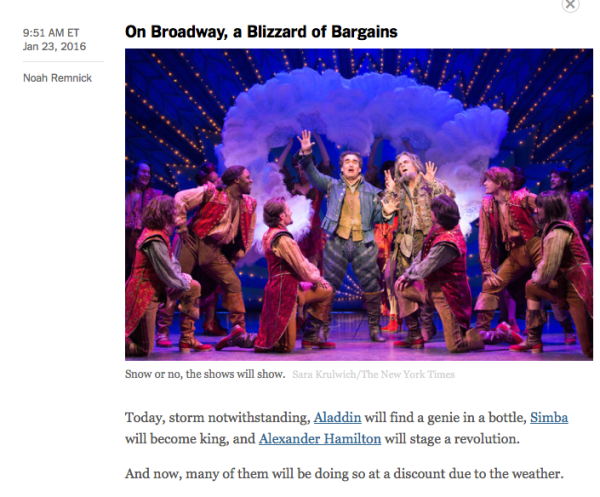

I don’t want to see headlines like “On Broadway, A Blizzard of Bargains.”

I don’t want to see it, because I know that it’s possible for snowplows and trucks to lose control on icy streets, and I know a whole lot of actors and box office workers and dressers and stage managers and bartenders and cashiers and people who had to work today, and I would feel a lot better about the odds of that truck losing control on the ice if all those people I loved had the chance to stay indoors.

In a state of emergency, friends, it is okay if the show does not go on. You are a person, and you are worth more — immensely more — than a 2pm matinee.

If you are a doctor or a nurse, a firefighter or an ambulance driver, a person who is actively involved in helping keep us all safe from this snowstorm: thank you.

If you had to go to work today, or if you’re still traveling: please be safe out there.

And if you go out to eat or drink tonight, tip your bartender and your waitstaff. Tip them very, very, very, very, very, very, very, very, very well.

**

Did you like this post? Help keep me writing.

Fffff

Sent from my MetroPCS 4G LTE Android :xxdffL

I think I just got my first official comment from someone’s butt.

Maybe they are buried in snow and “Fffff” is all they can say 🙂 Stay safe!

I share your appreciation for having a non-first-responder job, and I did tip the owner of the small Chinese restaurant who was open tonight (after the first two I tried were closed) and who was even still doing delivery – for an extra dollar an order. 😦 Thanks for the reminder of what’s important and why.

Snowed in in Bethesda MD … and living David Dudley’s vision of a blizzard.

This is interesting and I share your belief that there are times when its just not worth going out. On the other hand, us folks up north have a higher “tolerance” for what’s acceptable traveling weather and what’s shutting down some cities today might just be a tough day in some other places. I’ve also felt that rush, just exactly as you describe, driving to a workplace when you feel like you’re the only one brave enough to do it, a pioneer if you will! You nailed the description. It’s exhilarating for sure. I think in the end people need to use common sense and make the appropriate choice. Unfortunately sometimes workplace policy gets in the way.

Going through a snowstorm is like playing with fire. But you know, very cold fire. I agree with your points here, sometimes the show doesn’t go on, and that’s okay. It’s sad that I see so many people in my day to day life pressured by their employer (both inside and outside the entertainment industry) to come to work when it’s almost impossible. I’ll definitely make sure to tip extra these days!

As always, a beautiful and descriptive post 🙂

Stay Safe

Aisling

But its a blizzard, possibly the biggest that US east coast has had in last 30 years. How come companies are working???? There is a state of emergency in Washington too!

Great post. My opinion is that if you are not a first responder, you have no business being outside in a weather emergency. The people that went put everyone else in danger. Especially the first responders. Like you, I spent the day in my pajamas here in New York. And snacked way too much.

Here in Buffalo, NY, we’ve been missed by the blizzard, for once. But I totally agree with your post – unless you’re in a first-responder type job, just stay home. It’s not worth risking an accident. There are too many stories during blizzards of people who go out foolishly for something like a cup of coffee and then slide off the road. That’s why, in this area at least, driving bans are declared during really bad storms. Maybe you won’t get in an accident, but maybe you will get stopped during the driving ban, and is that $5 cup of coffee really worth a $150 ticket? I’ll just make coffee at home.

Here in the UK we’re all hoping for a snow day. The facebook pictures make it look rather fun but I don’t think people over here realise just how much work goes into keeping crucial services open when the weather turns.

Pingback: The snow must go on. | What the

Well said! And an excellent idea to tip your wait staff. We have seen our fair share of blizzards here in Nebraska, but people still forget what snow is like every year. Glad you didn’t have to go work! Snacking while wearing your comfy socks sounds lovely.

One of my first days as a new immigrant to Canada featured a snow day of epic proportions. Being the newbie, and a keener, I slogged to work (3 hours instead of the normal 20 minutes) – I got to the office to find only one other person there and he’d cross country skied to work!

I spent the remainder of the day getting home – lesson learned.

Stay safe, stay warm, and enjoy the enforced down time.

If that show can change peoples lives or even save a life or two by moderating attitudes … is it worth the calculated risks?

In South Africa we are having a second very dry year in a row and temps of up to 42 Celcius (107.6 Fahrenheit) Some areas have had some rain in the last few days

How about trading some of the snow for a few degrees of heat ?

Could we in Alaska have our snow back, please? We miss it.*

Seriously, though: I was a newspaper reporter in Alaska between 1984-2001 and never, ever got to stay home from work due to bad weather. Some white-knuckled moments occurred but I managed to keep it between the ditches. A few times I was involved in slow-motion fender-benders, aka “knowing the other guy is not going to be able to stop and trying to relax all your muscles in case his car his yours really hard.”

Generally speaking, I agree: Stay home if your boss permits it. Putting yourself at risk means that the first responders have yet more to do and they’re probably needed at the three-car crash vs. your slip-and-fall on the way to Wawa for a shorti hoagie.

*I moved back here in 2012. The past two winters have been noticeably short on snow, which just feels unnatural. Compare this to growing up in South Jersey, where snow that stuck was more of a maybe/maybe not.

Pingback: Favorite blog posts of the month #1 – Dalindcy – Personal blog

I enjoyed reading this post, you write so very well. Thank you for sharing 🙂

As someone who knows the feeling of going to work no matter what (as in risked my life to go earn a minimum wage paycheck), I appreciate this post more than you know. I have just moved out of Colorado, where I have friends who have made it to work the past few days through piles and piles of snow, and they have been heavy on my mind. I hope that someone other than myself, feels appreciated through your thoughtful written words.

This was beautiful, because it is so true and so important!

*sign so true. Especially in Chicago with wind chills that can knock your socks off! But I’m a Vet Tech so that means extra large snow suits and hot cocoa for me as I track to the ER

I really enjoy your blog and writing style. You are very witty.

I live in Florida, so I can’t relate, but I can empathize.

I love how you write! How do I write and what method of writing is most relative towards the blogging lifestyle? I am a newcomer and I want to learn how to include the audience with entrapping words. May you check out my blog and leave some advice for me?